There’s always an adjustment. A stretching. Strangely enough, to kids, none of this actually seems strange. For instance, the adjustment time of a child to country living is incredibly quick. Kids were made to stretch out. So, when given the space, they stretch! They inhale deep breaths into young lungs and take off at a run. They may look over their shoulder a lot at first, watching for that slow moving grown-up, but sooner than later, they’re rolling down grassy slopes and landing without a thought into a tangle of limbs at the bottom. Up they bounce to do it again. Grown-ups who have reached their full height—and may even be on the shrinking side—take a little longer to stretch. Some grown-ups are ready for it and may not notice their own growth. Those folks very rarely notice or appreciate the growing pains of others and dismiss the intense pain under the skin. They turn a blind eye or even scoff at the stretch marks their counterparts bear. What a shame. If there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that folks who bear stretch marks are often the ones extending grace when they recognize the marks on others.

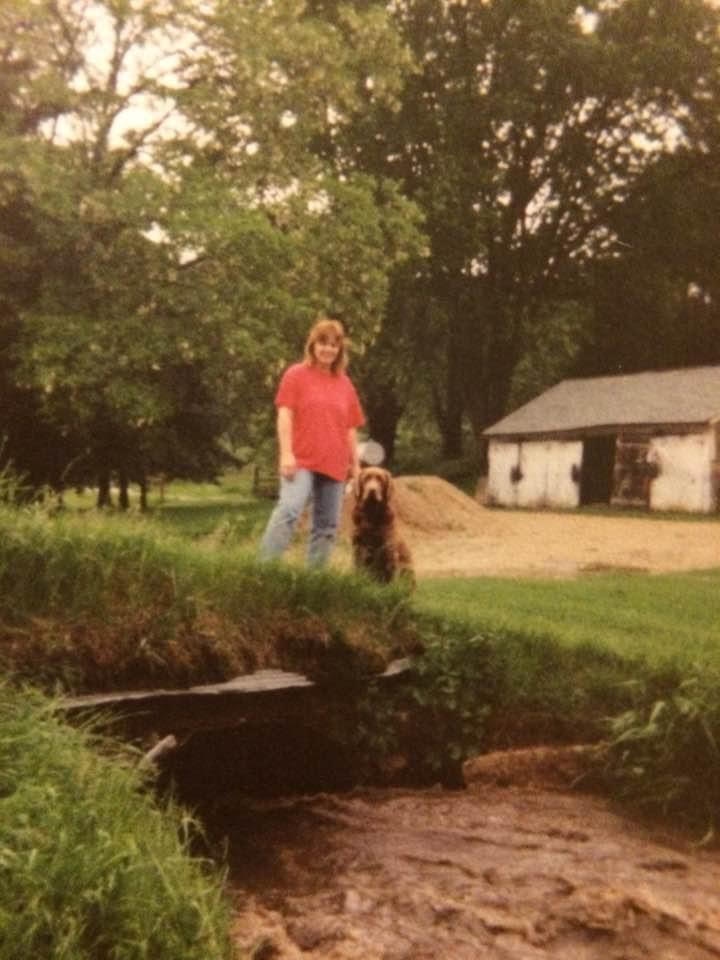

When I was a kid, we moved from city to country. My mom went from pollution and growing crime to manure scented “fresh country air”. She traded an adorably established place with an above ground pool complete with changing room and an under-the-sea mural she’d painted for mouse and bat infested walls and window sills full of hundreds of dead flies. Leaving behind a few well cared for buildings surrounded by lovely, established oaks and maples, she encountered a spattering of sheds in various states of disrepair and the planting of seedlings on rolling hills of reclaimed farmland. She went from walking down a few dozen feet of blacktop to get the mail to a quarter mile stroll down washed out gravel only to find the mailbox had been run into again by the latest snow plow or drunk on his way home from Soggy’s bar.

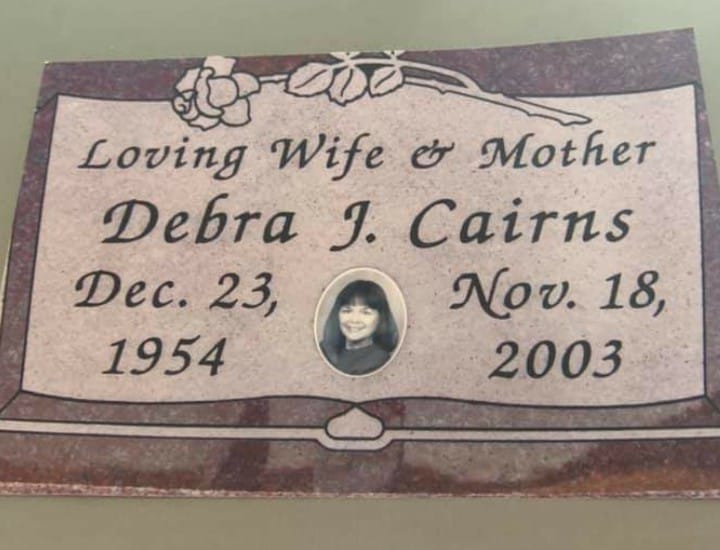

Sometimes I intensely want to ask Mom more about her life. When I’m not thinking about it, it’s fine. I often think that she left her mark and there’s no need to know everything. I don’t need to know about her highschool life. I don’t need to know about what she liked to do as a kid. Sometimes, though, I just want a little more. I wish I could see what shaped her into the person she was. What was it that comforted her so deeply that she was so intent on loving others? Or did a lack of comfort teach her? Was she intent on not allowing that hurt to reach her own loved ones?

I have a memory of Mom very shortly before she went in for the surgery that would discover the cancer that would eventually claim her life. She called me to her and sat on the step leading from the garage into the room she called “the breezeway”. I sat next to her and she began to apologize. She told me she was sorry for how she’d acted and how she’d been angry. She said she thought it was likely from fear–

Then someone called her from inside the house, and we never got back to that conversation. Gosh, if that doesn’t imprint on a body to be sure to finish your important conversations, I don’t know what does.

I don’t know everything she’d planned to say to me that day, but, all these years later, I have never forgotten that moment of intentionality to make sure I knew her devotion and love. She created an atmosphere of love and faithfulness. I knew she was my mom. I knew she meant to be the best mom she could be. I was fourteen years old then and definitely thought I knew better than my mom. I suffered years of regret after she died knowing that I had never asked her forgiveness for being the extremely pigheaded, authoritarian sister who knew better than she did how to parent my little brother. I had let that silly “right-ness” get between me and Mom. It wasn’t until much later that I realized she hadn’t held it against me. She knew just where I was, loved me, and forgave me even before I’d begun. It didn’t matter that I was rebelling, because she was in it for the long haul. She was faithful and loving. I have often wished she’d have put me in my place and told me she was the mom and that I should cool it, but I couldn’t mold her into the person I needed or wanted. That was never my place. It is very likely she never would have gotten that through to me anyway. I was fourteen, for pete’s sake. I know now that she was operating in love, growing herself, and doing her best with the understanding she had. Looking back, she certainly was leaps and bounds ahead of me as I stand even now.

Mom left us with a grace that I can hardly understand. Now that I have kids, I cannot fathom what it would feel like to know I was leaving them behind, especially with my first hand knowledge of the hardships that can and do come for a child after losing a beloved parent. It’s a wandering thought that frequents my mind. I have also wondered how she felt after losing her own mom as an adult. I can’t ask her and don’t feel like I have reliable sources to question because, frankly, every single person is biased. I am biased. Everything I see is through my lens. My lens certainly doesn’t feel reliable to tell Mom’s story. My childlike lens saw things with the rose colored glasses of a happy childhood.

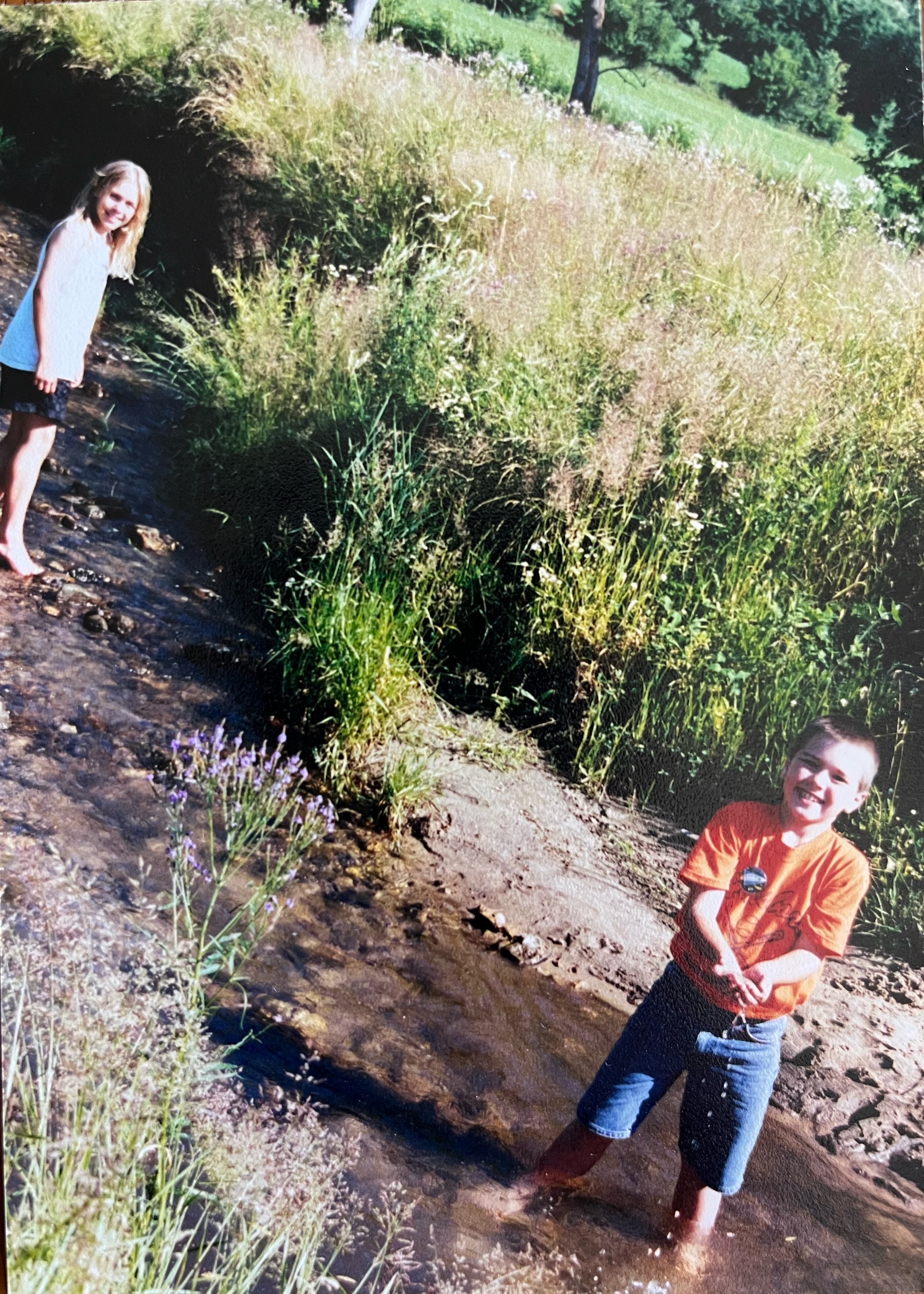

For instance, I loved Chicken Hollow Road farm. This farm that we moved to shortly after making the big move up north to Yuba was absolutely the best place a child could live. We played in old, broken down outbuildings, had fields to roam, a babbling creek filled with crayfish and tadpoles, a chicken coop, huge shady trees, and a tired old farm house where we could really live without worrying about being too hard on it. It was a place to stretch. We had so much to explore and ample opportunity to try raising different animals with little fuss. If they didn’t work out, well, at least we hadn’t built a shed just for them. We had ducks and a goat and dogs and chickens and even a horrible donkey named Crimson for a bit. I loved every experience. It was a taste that we could try and then send back to the chef–or another farmer–when we found it was not really our preference.

Looking back with my adult lens, Mom had to do her laundry in a cellar whose only entrance was on the side of the house. The floor was dirt. The walls were dirty. The other cellar door led to a dirt cellar for food. We had to lime it. Seriously, we actually lived in a home with cellars you still had to whitewash! As a kid, it was awesome. I had read about this stuff in my old books! Now, I look back at the trouble mom had to go through with all the securely lidded, mouse proof bins, the doors that wouldn’t fasten shut, the horrible mold that began coming up through the vents giving me a cough so I had to sleep in the living room because my bed was just above that cellar. I remember and cannot help but think my mom was remarkable. Maybe she complained every day to my dad. I have no idea. I just know she cultivated a world around us that caused her little shoots to grow into healthy, robust little plants. She fostered curiosity in the world around us and a deep seeded knowledge that God loved the world He’d created and He loved us.

When she was dying, she showed grace to all around her. She did not grieve as one without hope, and it seems to me she had lots of cause for grief, leaving behind 6 kids and a very full life. Maybe she was given an extra measure of grace and that measure she felt compelled to pour out even as she received it. What a heart of love! She had been separated–intentionally or not, I never knew–from her siblings for most of her later years, but when it was time to go, she wanted nothing more than to pour out a measure of love and grace to all of them once more, to show the love of Jesus once more and for all. She asked for Amazing Grace to be played at her funeral in hopes that it would remind her siblings of their own father’s funeral. Perhaps to draw to mind that death waited for no man.

Mom was funny. I loved her humor. When she was dying, someone asked if they could bring her anything to drink, and she asked for a coke. They asked if she preferred regular or diet, and she wryly responded that she didn’t drink diet as it gave you cancer. What a doll.

A few months ago, when my kids watched the live action popeye with Robin Williams, I could have cried as they giggled and burst out laughing at the movie my mom had laughed over. I can still hear her singing along with Olive Oil’s shrill voice, “…but he’s large!” As always, I question my memory. Did Mom really love it, or did she just chuckle behind her knowing, laughing eyes as she got some joke that had gone over my head. Either way, I remember the pleasure of shared mirth.

Once when she was recovering in the hospital after her surgery to remove the cancerous tumor, she called to check up on us. Her food arrived while I was still on the line. She told me to stay on so I could listen to her make yummy noises. That is one of my most treasured memories. I love that it was just the two of us. She had ham and potatoes, by the way. I like remembering every detail. I feel her mom-ness in that whole experience.

On a day when she drifted sort of half in, half out of lucidness, we were brushing her hair and telling her how nice she looked. She, her humor never quite diminished, asked, “Do I look radiant?” Who could resist that woman?

Mom’s funeral procession was the longest I’ve ever seen. The funeral was packed, and it’s no wonder. I have to say Mom was an attractive woman. She was beautiful, but that’s not the kind of attraction I mean. She had a love for beauty, a longing for others to see it, and the charisma to help us get there. I haven’t met a single person outside our family who didn’t have a gleam in their eye when they talked about my mom. It’s like they can’t help but remember what a special and life giving person she was. She still is.

Mom had beautiful hands. They were not very pretty. They were the hands that had known work. Sometimes I look at my own hands and wish they were nicer, but, more often than not, I catch a glimpse of Mom in my rough, veiny hands–as I know a few of my female relatives have–and I’m more thankful than ever to have them as a ready reminder. I remember and see only beauty in my memory. The saying “I know it like the back of my hand” holds a tremendous amount of sweetness for me.

The Mother’s Day before Mom died, my sister, Jacque, played Celine Dion’s song “Mama”. “…goodbye’s the saddest word I’ve ever heard…” I gave her a hard time because it sounded like she was saying mom was dying. How little did we know. I remember thinking, “What if this is the last Mother’s Day we have mom?” Then it was. It’s strange how many of those moments I remember now, almost a foreshadowing. Did you know you could feel guilty about premonition? We don’t ask for the odd feeling, but we feel responsible just the same. Sometimes I’ve been thankful for those moments of preparation, as though they were a special dispensation from our loving Heavenly Father. What a strange world grief is.

We don’t know what to say to someone who is grieving. The “rawness” wears off—at least in the public’s eye—and that person seems to go on with their life. Everything becomes “normal” again. What often never comes is the opportunity for that person to tell their story, feel heard, and so be able to fully heal from things long forgotten, or so dormant that they take effort to recall. This monumental event causes a huge character arc in the life of the griever but is rarely truly shared. The story never comes to light, not because they weren’t willing to tell it, but because no one asked. That’s the thing about grief stories: they feel weird to tell unless someone asks and really wants to hear. Talking about the dead brings an odd mixture of confusion, sympathy, and awkwardness at any attempt to bring up that loved one’s name.

Mom always told me that someday I would write our story. But when someone dies young leaving so many behind, their life is somehow now defined by the fact that they were snuffed out too early. How do you tell the story of someone who simply lived simply? The stories I’ve told here all seem so insignificant in isolation. Any number of people who knew her would wonder why I didn’t instead include other stories, but I’m beginning to think that’s sort of the point. Lives seem to be that way. It’s not the big events that form a person. It’s the small reminders of God’s love and goodness. It’s the little moments and seeds scattered and evenings spent watching sunsets and minutes bumping elbows while washing dishes in tiny kitchens. This is the sum of a life. To notice all these details is to really know the person. With knowledge comes the ability to love.

It’s good to remember and recall. It’s good to do it by yourself and with your family and friends. Remembering together helps you notice the stretching that’s been happening beneath the surface that you may not have otherwise noticed. It’s ok to get some of the memories wrong. It’s ok to fumble through the dates and locations. Sometimes that’s half the fun of them. I think it’s important to hash it out. It’s important to forgive the misunderstandings, because, eventually, the dates and locations fade away. The body returns to dust. But the spirit remains and is cherished by those she has touched with her life and love.

Leave a comment